2-Channel video Installation for 4K Projection and Discoball, 40:00 min, UHD Video, Stereo, 2024

Music: Bastian Hagedorn

| – |

The video installation Paradise Now (2024) travels to various large-scale construction projects in Vietnam and Cambodia that share the promise of utopia: Ho Thuy Tien, a 50-hectare water park opened in 2004 8 kilometres outside Hué, the former imperial capital of Vietnam. A huge, walk-in dragon sculpture still stands in the middle of a lake in the park, which was built at a cost of 3 million euros and is now abandoned. Another filming site is the Bokor Hill Station near Kampot in Cambodia: Since 2008, hotels, restaurants and a golf club have been built here on ruins from the French colonial era under the management of the Cambodian Sokimex Group. The Thansur Bokor Highland Resort Hotel and Casino opened in 2012, and the entire mountain plateau will be redeveloped over the next few years, including the construction of Bokor City for Chinese exiles. Further filming locations include the disco club “Heart Of Darkness” in Phnom Penh, the Khmer “Bat Pagoda” in Sóc Trăng, the premium beach club Kep West and the former prison island of Côn Đảo, which is set to become Vietnam’s next luxury tourist destination.

Inke Arns, short text from the exhibition publication "The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16 March - 1 September 2024

Die Videoinstallation Paradise Now (2024) begibt sich zu verschiedenen baulichen Großprojekten in Vietnam und Kambodscha, die das Versprechen von Utopie verbindet: Ho Thuy Tien, ein 2004 eröffneter, 50 Hektar großer Wasserpark 8 km außerhalb von Hué, der ehemaligen imperialen Hauptstadt Vietnams. Noch heute steht in dem für 3 Millionen Euro errichteten und heute verlassenen Park eine riesige, begehbare Drachenskulptur inmitten eines Sees. Ein weiterer Ort ist die Bokor Hill Station in der Nähe von Kampot in Kambodscha. Auf Ruinen aus der französischen Kolonialzeit entstehen hier seit 2008 unter Leitung der kambodschanischen Sokimex-Gruppe Hotels, Restaurants und ein Golfclub. Das Thansur Bokor Highland Resort Hotel und Casino öffnete 2012. In den nächsten Jahren soll das gesamte Plateau des Berges umgestaltet werden – unter anderem soll dort die Planstadt Bokor City für chinesische Exilanten entstehen. Weitere Drehorte sind die Diskothek „Heart Of Darkness” in Phnom Penh, Tempelanlagen der Khmer in Sóc Trăng, der Premium Beach Club Kep West sowie die ehemalige Gefängnisinsel Côn Đảo, die sich zu Vietnams nächstem Luxusreiseziel entwickeln soll.

Inke Arns, Kurztext aus der Ausstellungspublikation „The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16.3.- 1.9.2024

| – |

One might venture so far as to say that Niklas Goldbach has not taken a single photograph of a human being in his works. Which, considering his background in sociology and a photography practice spanning nearly two decades, testifies to an admirable persistence and a sense of observation focused not on our interactions, but on what structures our existence: a sense of space, architecture, and social engineering.

For Paradise Now (2024), Goldbach prepared a slow-sipping cocktail of views of massive construction projects in Cambodia and Vietnam. Some in the making and imposing in their scale, others defunct and resembling vestiges of past civilisations that thrived just a while ago. As Inke Arns put it: Those “various large-scale construction […] all promise utopia. The first is Ho Thuy Tien, a 5 hectare water park that opened in 2004 just 8 kilometres outside of Hué, the former imperial capital of Vietnam. To this day, a huge, walk-in drag sculpture, built to the tune of three million Euro, stands in the middle of a lake in the now abandoned park. Another location is Bokor Hill Station in Kampot in Cambodia, where the Sokimex Group has been building hotels, restaurants and a golf club on ruins from the French colonial era sin 2008. The Thansur Bokor Highland Resort Hotel opened in 2012, and the entire mountain plateau is to be redeveloped over the next few years, with plans including the construction of an entire city (Bokor City).” All this culminating in an ecstatic shot of a rave-fuelled club in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, its name: Heart of Darkness.

Goldbach’s journey echoes a tension between the major narratives in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) and Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), each of them tackling universal topics through the events of their time. “Coppola’s film …”, says Goldbach, “served as a loose inspiration for my filming locations: the Mekong Delta, the beaches, the military bases, and colonial villas. While Conrad’s novella was the literary template for Coppola’s film, in my video, it becomes a filming location for the visual climax of the video, the first time we see people: The Heart of Darkness is the longest running gay club in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh and one of the city’s most popular nightlife attractions.”

But more than anything, Goldbach’s work is a novella about the endless cycle of creation and destruction that is told through the fate of architectural structures. He says: “Alongside the more existential waltz of construction and decay, the tourism and real estate industries are transforming these once ‘exotic’ branded locations into either homogeneously designed and globally accepted boutique hotels – or into concrete beach deserts. To me, everything we build is essentially a sandcastle at high tide – temporary and sometimes beautifully fragile.”

The Black Box at Wschod New York presents the US premiere of the most recent film of Berlin-based artist Niklas Goldbach commissioned by Inke Arns and first shown in March this year 2024 at Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV) in Dortmund, as part of Goldbach’s largest institutional exhibition today.

Krzysztof Kościuczuk, exhibition text "The Black Box" @ Wschod Gallery New York, 5/2024

| – |

Into the Darkness.

Niklas Goldbach in conversation with Krzysztof Kościuczuk

Krzysztof Kościuczuk (KK): Paradise Now is your most recent video work commissioned for the exhibition at Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV) in Dortmund. It is a slowly-unfolding journey through ruins and construction sites. What convinced you to turn those sites into a narrative?

Niklas Goldbach (NG): Paradise Now is the result of my fascination with the ephemeral nature of human architectural ambitions, especially those marketed as idyllic or even ‘paradisiacal’ structures but which end up as abandoned investment ruins. Through sites such as Ho Thuy Tien, a failed amusement water park with a massive dragon sculpture hauntingly overseeing a lake, a €3 million project now lying in ruins, I‘m fictionalizing the shattered dreams of its past. But my perspective is sociological rather than moral, and so the work highlights wider societal shifts in these areas and regions through the abstract lens of property, real estate and colonialism.

KK: Tell me more about some of the other locations we encounter?

NG: The video begins with the arrival of an airplane on the former Vietnamese prison island, Con Dao, where the French built their first prison in 1861. Today, the island is poised to become a popular tourist destination, yet it remains a place of pilgrimage for the Vietnamese.

This is followed by a sequence showing ruins, including former villas, filmed in the Cambodian province of Kep. Under French rule, the province became Cambodia's very first beach resort. Founded in 1908 as Kep-sur-Mer, it was a popular destination for the French and Cambodian elite until the early 1970s. Today, you can still see the ruins of the hundreds of colonial and modernist villas that once dotted the coast.

Next comes Bokor City, not far from Kep, another particularly dark and disturbing example of contemporary architectural ambitions. This new city in the making, developed by Chinese investors who have been granted a 99-year lease on the grounds of a former French colonial military base inside a Cambodian national park, will cover some 9,000 hectares. Located some 1,000 meters above sea level, the project transforms the military buildings and the nearby elite retreat into an urban area for an exclusive clientele. This project is one of the most cynical examples of the inherent tensions between urban development and environmental protection. It also resonates with my concerns about sustainable development and the environmental impact of profit-driven real estate projects. The video ends with three camera shots of a newly opened luxury beach restaurant next to the traditional crab market in Kep.

KK: This journey echoes that of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899) and, subsequently, Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979), adding a new layer to those epic narratives.

NG: Aside from the title being an obvious reference, Coppola's film also served as a loose inspiration for my filming locations: the Mekong Delta, the beaches, the military bases, and colonial villas. While Conrad's novella was the literary template for Coppola’s film, in my video, it becomes a filming location for the visual climax of the video, the first time we see people: "The Heart of Darkness" is the longest running gay club in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh and one of the city's most popular nightlife attractions.

KK: There is a cycle of decay and creation in the film; do you see it as your comment on exoticisation and self-exoticisation or a general remark about human existence?

NG: Alongside the more existential waltz of construction and decay, the tourism and real estate industries are transforming these once 'exotic' branded locations into either homogeneously designed and globally accepted boutique hotels - or into concrete beach deserts. To me, everything we build is essentially a sandcastle at high tide - temporary and sometimes beautifully fragile.

KK: Music and sound are key components of your moving image works; tell me who you worked with this time?

NG: I told Bastian Hagedorn, whose work I have known for a number of years through his own musical endeavors as well as through his work with visual artist Henrike Naumann, about the project. He immediately connected with my more abstract vision of creating a cinematic essay film without text and with the exclusion of human presence from large parts of the visuals. He came up with a musical concept that intensified the focus on the architectural structures as well as the natural processes that reclaim these spaces. We also incorporated some of my field recordings, but for me, Bastian's hauntingly beautiful soundtrack adds a new, highly individual layer of meaning and rhythm to the work.

KK: Tell me how Paradise Now was originally presented in March this year?

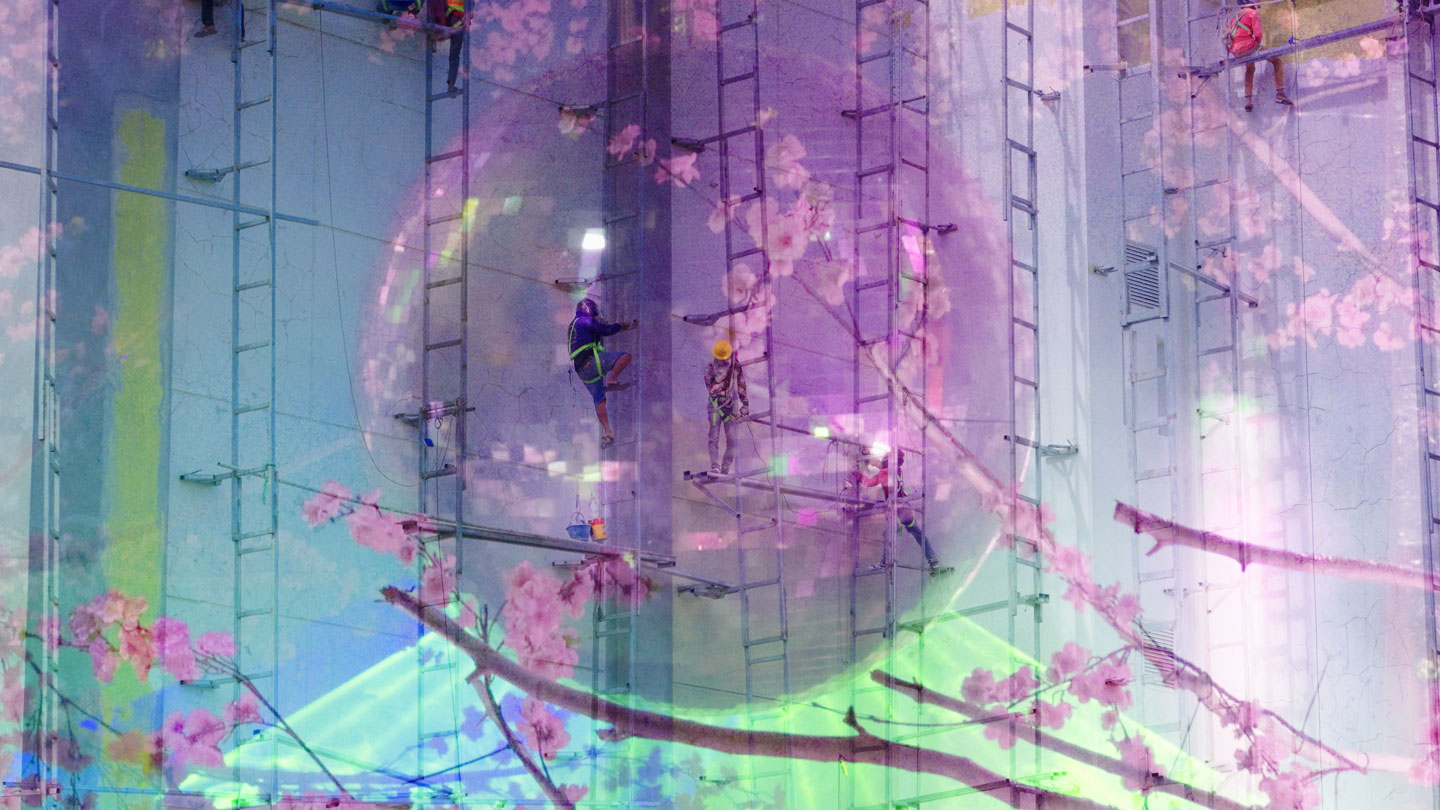

I am currently showing the work as part of my exhibition The Paradise Machine at Hartware Medienkunstverein (HMKV) in Dortmund, curated by Inke Arns. There I presented the work as a two-channel video installation. The video projection is synchronized with a second projection on a rotating disco ball, which extends the video immersively into the entire exhibition space. In front of the main projection is an empty stage—a laconic invitation to dance to Bastian's music, perhaps the last party of the season.

KK: Video works are one part of your practice; the other is still images. Can you tell me how they are connected?

NG: Both my videos and my photographs are made with the same camera, but each medium examines time and space in very different ways. While video allows me to explore vast and complex structures like the abandoned water park in Paradise Now, photographs can be re-contextualized through the arrangement and order in which they are presented. For example, my ongoing series Permanent Daylight, initiated in 2013, examines architectural sites and landmarks around the world. To date, the series consists of over 450 photographs taken at different locations globally. The series explores the concept of growing global interconnectedness: the selected sites have either been created or defined by human culture—yet they are conspicuously devoid of any evidence of human presence. I present these photographs as “portraits”, in individually titled and fixed constellations that create new essayistic contexts and narrative associations between the images.

| – |

The first words uttered in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) were those of the protagonist speaking about the place where his journey originated: “‘And this also,’ said Marlow suddenly, °‘has been one of the dark places of the earth.’” One might venture so far as to say that Niklas Goldbach has not taken a single photograph of a human being in his works. Which, considering his background in sociology and a photography practice spanning nearly two decades, testifies to a persistence and a sense of observation focused not on our interactions, but on what comes before and structures our existence: space, architecture, and social engineering […].

For Paradise Now (2024), his most recent work, Goldbach prepared a long cocktail of views of sprawling construction projects in Cambodia and Vietnam, some in the making, others abandoned, resembling vestiges of past civilizations: all culminating in an ecstatic shot of a rave-fueled club in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, its name: Heart Of Darkness. Goldbach examines how human desire can propel our actions, while rarely adopting a direct moral stance. His readings of modernity, identity, the colonial and decolonial in their complexity, the exotic and self-exoticization, as well as the unconditional implication of both the viewers and himself in the narratives we are invited to experience, are never one-sided: at the verge of permanent daylight there is invariably a brooding darkness.

Krzysztof Kosciuczuk, excerpt from "Niklas Goldbach: The Paradise Machine", Exhibition Review, Camera Austria No.166, p 76

| – |

[…] The endless water slides of Aqua Mundo, which in the video Into the Paradise Machine have been left out just like the people, find their ghostly counterpart in the shots of the disused Vietnamese water park Hồ Thủy Tiên, which appears in Goldbach’s latest video, Paradise Now. In the former, which combines exterior and interior shots of the bungalows of three different Center Parcs in such a way that they become undistinguishable, Goldbach seems to unearth the facilities’ original modernist form beyond their current postmodern transformation by the spectacle – and one hardly understand how, even in the aerial shots, he managed to keep the dominant glass roofs and domes of the entertainment facilities out of the picture. It works like a kind of reverse palimpsest. In this video, time seems to have been turned back, and only the smoke rising here and there from the chimneys indicates that someone is there.. At times, it feels like nature is in the process of reappropriating the deserted territories – a process well under way in Hồ Thủy Tiên. Goldbach here again clearly went to great lengths to avoid or remove all human presence from his images, since unlike what they suggest, the huge ruin is an extremely popular tourist attraction […].

Iris Dressler, Excerpt from "Soft Cops",

Essay of the exhibition publication "The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16 March - 1 September 2024

[…] Die endlosen Wasserrutschen des Aqua Mundo, die in dem Video Into the Paradise Machine ebenso ausgeblendet werden wie die Menschen, finden ihre geisterhafte Entsprechung in den Aufnahmen des stillgelegten vietnamesischen Wasserparks Hồ Thủy Tiên, die in dem jüngsten Video Goldbachs, Paradise Now, zu sehen sind. In Ersterem, das die Außen- und Innenaufnahmen der Bungalows dreier verschiedener Center Parcs kaum voneinander unterscheidbar in eins setzt, scheint Goldbach die modernistische Urform der Anlagen jenseits ihrer aktuellen postmodernen Überformungen durch das Spektakel aufzusuchen – und man begreift kaum, wie er es geschafft hat, dass selbst in den Luftaufnahmen die dominanten Glasdächer und -kuppeln der Entertainment Facilities nicht ins Bild geraten. Es ist wie eine Art umgekehrtes Palimpsest. Die Zeit scheint in diesem Video zurückgedreht und nur der Rauch, der hie und da aus einem Kamin aufsteigt, verweist darauf, dass da jemand ist. Mitunter entsteht der Eindruck, als sei die Natur im Begriff, sich die menschenleeren Territorien wieder anzueignen – ein Prozess, der in Hồ Thủy Tiên bereits weit fortgeschritten ist. Auch in den Bildern dazu hat Goldbach die Menschen offenbar mit viel Aufwand vermieden oder entfernt, denn bei der riesigen Bauruine handelt es sich um eine äußerst beliebte Tourist*innenattraktion, wovon in den Aufnahmen nichts zu merken ist […].

Iris Dressler, Auszug aus „Soft Cops", Essay der Ausstellungspublikation „The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16.3.- 1.9.2024

| – |

[…] Paradise Now (2024) travels to various large-scale construction projects in Vietnam and Cambodia that hold the promise of paradise on Earth. The first is Ho Thuy Tien, a 50-hectare aquatic park that opened in 2004 just 8 kilometres outside of Hué, the former imperial capital of Vietnam. To this day, a huge, walk-in dragon sculpture stands in the middle of a lake in the now abandoned park, which was built to the tune of €3 million. Another location under survey is Bokor Hill Station near Kampot in Cambodia, where hotels, restaurants and a golf club are being built on ruins from the French colonial era since 2008. The Thansur Bokor Highland Resort Hotel opened in 2012, and the entire mountain plateau is to be redeveloped over the next few years, with plans including the construction of an entire city (Bokor City). Paradise Now literally takes viewers on a tour of the various stages of the paradise machine: decay is followed by construction is followed by decay is followed by construction... The rotten slide and pool area at Ho Thuy Tien in particular seems to forebode the future of the Centre Parcs’ subtropical bathing paradises […].

Inke Arns, excerpt from "The Paradise Machine - Of Towers and Foundation Pits in the Works of Niklas Goldbach"

Introductory text to the exhibition publication "The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16 March - 1 September 2024

[…] Paradise Now (2024) begibt sich zu verschiedenen baulichen Großprojekten in Vietnam und Kambodscha, die das Versprechen eines irdischen Paradieses verbindet: Da ist einerseits Ho Thuy Tien, ein 2004 eröffneter, 50 Hektar großer Wasserpark 8 km außerhalb von Hué, der ehemaligen imperialen Hauptstadt Vietnams. Noch heute steht in dem für drei Millionen Euro errichteten und jetzt verlassenen Park eine riesige, begehbare Drachenskulptur inmitten eines Sees. Ein weiterer Ort ist die Bokor Hill Station in der Nähe von Kampot in Kambodscha. Auf Ruinen aus der französischen Kolonialzeit entstehen hier seit 2008 Hotels, Restaurants und ein Golfclub. Das Thansur Bokor Highland Resort Hotel öffnete 2012. In den nächsten Jahren soll das gesamte Plateau des Berges umgestaltet werden – u. a. soll dort Bokor City entstehen. Paradise Now nimmt uns quasi mit zu verschiedenen zeitlichen Stadien der Paradiesmaschine: Auf den Zerfall folgt der Aufbau, folgt der Zerfall, folgt der Aufbau … insbesondere der verrottete Rutschen- und Poolbereich von Ho Thuy Tien scheint die Zukunft der subtropischen Center Parcs-Badeparadiese vorwegzunehmen […].

Inke Arns, Auszug aus „Die Paradiesmaschine - Von Türmen und Baugruben in den Arbeiten von Niklas Goldbach",

Einleitungstext zur Ausstellungspublikation „The Paradise Machine", HMKV Dortmund, 16.3.- 1.9.2024

| – |

Video by Niklas Goldbach

Music by Bastian Hagedorn

Camera, Edit, Postproduction: Niklas Goldbach

Sound-Design: Niklas Goldbach & Bastian Hagedorn

Executive Co-Producer: Viktor Neumann

Filmed on location in Kep Municipality, Preah Monivong Bokor National Park, Bokor City, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Filmed on location in Hué, Côn Đảo, Sóc Trăn, U Minh Hạ National Park, Vietnam

in 2023/24

Co-produced by HMKV Hartware MedienKunstVerein Dortmund

in the framework of the exhibition THE PARADISE MACHINE curated by Inke Arns

VIDEO TRAILER

|

EXHIBITION VIEWS

Exhibition views:

"Niklas Goldbach: The Paradise Machine"

HMKV Hartware MedienKunstVerein Dortmund, 16.3. - 11.8.2024

Curated by Inke Arns

Photos 3-6: Roland Baege

|

VIDEO STILLS